Optimism and its dark side: the need for scepticism in the age of Covid-19

In late March, as Covid-19 swept through Europe like a medieval plague, throwing country after country into a disarray not seen in almost a century, a strange – but not so surprising – phenomenon occurred. News outlets all over the world, egged on by gushing social media influencers, reported that cities were being reclaimed by wild animals. In Venice, dolphins and swans were spotted swimming through the canals. In India, newly emboldened elephants were photographed drinking corn wine and then sleepily recuperating in a farmer’s field. Soon the Edenic images, which were circulated by millions of people, became a meme: “Nature is healing we are the virus”.

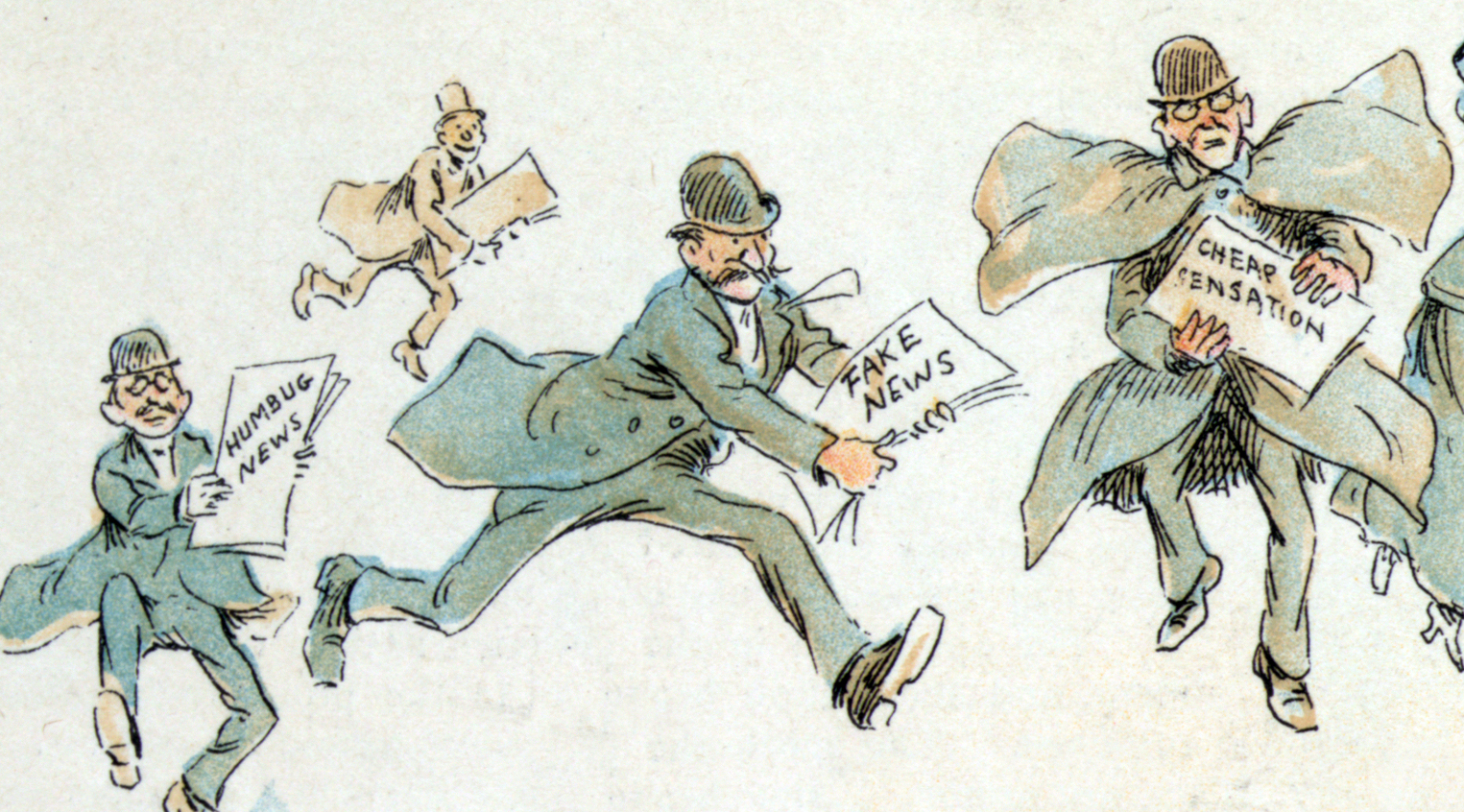

Eventually the sugar-coated disinformation was put to an end by National Geographic. “The phenomenon highlights how quickly eye-popping, too-good-to-be-true rumours can spread in times of crisis,” said the magazine’s Natasha Daly. “People are compelled to share posts that make them emotional.”

The animal-centric posts were innocuous in this case, but their allure reveals why – in these tumultuous times – one needs to be especially on guard against positive fake news. Throughout history our ability to see the bright side of things has helped us face adversity and develop countless new technologies. Nevertheless, issues have frequently tended to arise as a result of our incautious optimism. In fact, when it comes to real-world decision-making, wishful thinking almost always clouds our judgement.

Psychologists call it “confirmation bias”: the tendency to see the world as we want to see it, not as it actually appears. Occasionally this kind of bias makes us interpret externals in a Disneyesque, overly saccharine way, and that’s where things can get sticky.

In its most extreme form, this kind of deeply ingrained egoism fosters conspiracy theories and groupthink. It also leads well-meaning people to be exploited by cult leaders, scammers, trolls, and other online and offline predators. Today, however, it’s much easier to succumb to this kind of manipulation than ever before. More and more individuals are insulating themselves from the outside world, looking to the internet as a respite from the invisible terror without. As the popular fact-checking site Snopes recently noted: “We’re seeing scores of people, in a rush to find any comfort, make things worse as they share (sometimes dangerous) misinformation.” In this context optimism and sentimentalism – ordinarily good things – can become poisonous. As one physician once said: “The dose makes the poison.”

Now is the time for cool-headed, critical thinking. Risks need to be evaluated and solutions developed, carefully and concisely. Like scientists who meticulously generate, contrast, and compare theories, policymakers and their teams need to be able to challenge and weigh their own preconceptions, leaving space for innovation. This kind of scepticism also applies to those who want to defend against disinformation peddlers, fraudsters, and charlatans. One needs to be able to stand aside and ask himself: “Is this what’s really happening, or is it just want I want to see?”

By turning this into a reflex, one becomes better suited to see the playing field, so to speak, for what it is. The mirage fades away. The fantasy castle and rollicking unicorns vanish in the daylight, and in their place emerges a winding path that, despite its dizzying length, represents the most viable way forward.

By Andrew Manns